And Now For Something Completely Different

As it turns out, my main hobby isn't miniature wargaming. It is in fact indoor freeflight model airplanes. Bet you didn't expect that coming, but its true.

As it turns out, my main hobby isn't miniature wargaming. It is in fact indoor freeflight model airplanes. Bet you didn't expect that coming, but its true.

Aviation has been in the family blood literally since the dawn of powered flight when my great-grandfather assisted the Wright Brothers at their bicycle shop in Dayton Ohio. Since then, my grandfather served in Korea as a mechanic on an escort carrier working on Corsairs, and later went on to become a national champion radio-control flyer. My dad got into control-line models and well as outdoor and indoor freeflight, also ranking high in international competitions and writing several books and articles.

Airplanes have always been my first hobby love. Much to my mother's dismay, wings, rudder and fusealage were among my first words, thanks to a heavy indoctrination plan on my dad's part. I built my first model airplane when I was five and have never stopped building them except regretfully in the past few years.

Airplanes have always been my first hobby love. Much to my mother's dismay, wings, rudder and fusealage were among my first words, thanks to a heavy indoctrination plan on my dad's part. I built my first model airplane when I was five and have never stopped building them except regretfully in the past few years.

Like my dad, I've taken to indoor freeflight as my model airplane sub-division of choice. It really tests your skill as a builder as well as poses interesting engineering challenges. The object of indoor (and indeed outdoor) freeflight is flight duration. You are going for the longest time in the air. To do this indoors you have to trim the aircraft's controls (thrust, elevator, wash, power, etc) to fly in a circle, ascending slowly so that you don't hit the ceiling. With freeflight, you have to consider all of this as you construct your aircraft.

Indoor freeflight has in itself several classes of competitions. There is endurance events and scale events. Endurance aircraft are purpose built for time. The bear no resemblance to real aircraft, but rather are built from super light balsa, covered with a material that is 4-5 microns thick, and weigh no more than a gram. They are powered by rubber bands and some can achieve flight times over 60 minutes!

Scale models are what my dad and I tend to fly. These are built to replicate actual aircraft, such as WWI fighters, etc. My personal time period preference is pioneer aircraft such as the Wright Flyer.

Yesterday I was hit with the desire to build an endurance aircraft called a Mini-stick. These are tiny models, often referred to as 'Parlor Flyers' as they are designed to be able to fly in your living room. I don't have a facility to fly my usual scale aircraft, so I thought building a Mini-stick for my living room is the next best thing.

If you are interested, there are several Mini-stick plans out there on the web available free. They are quick and simple to build, as I'll demonstrate below. But if its your first model, allow for some extra time :) And again, I apologize for the remarkably bad photos. I miss my computer,... I feel helpless without my Adobe programs!

Step 1: Pin the plans down.

The first step is to score some plans. I'm using Rob Romash's Poonker plan found here: http://www.indoorduration.com/Poonker.htm

You will notice that Ive taken some liberties with the plan, including the rudder, and the wing's dihedral. These are modifications made with the aim of both a simpler build and to adapt to my extreme indoor (living room) flying space.

Pin the plans to a piece of insulation foam or ceiling tile with a sheet of baking paper or clear plastic wrap over it. This allows you to glue your pieces together without sticking to the plans.

Next I cut all my wood. I use balsa wood. I start with a sheet and slice my own sticks rather than use pre-cut ones as they are quite expensive. On that note, I should mention that this plane uses about $1-2 (USD) worth of materials... pretty good value for money!

I have a nifty plastic airfoil template which I use for all my projects. I will see what I can do to post up a plan for it in the future. I used the template to cut about a dozen ribs and several sticks about 1mm x 1mm (1/32").

Once all of the pieces are cut you can start the assembly project. Pin the wing's and stab's leading and trailing edges down first. Don't put the pin through the wood as it will likely break it or at the very least severely weaken the wood. Instead, use a simple 'X' configuration with a pair of pins to keep it snuggly fixed in place. Make sure that sticks are nice and straight.

Place a single pin vertically on the outside edge where there is a wing rib so that the wood doesn't bend when you but the rib up against it. Otherwise, you'll get wonky-shaped wings.

With the leading and trailing edges pinned down, cut the ribs to fit and place them between the stick according to the plan. Make sure that they are vertical at 90-degrees. I use a small right-angle template to make sure that each is set properly.

Once these are in place use a small bit of wood or something similar (I use a thin steel wire rod) to apply glue. Simple PVA works well for this purpose, but you'll want to water it down to about 50% so that the glue can seep into the joint's pores, firmly holding the pieces together.

NOTE: Do NOT use superglue! It'll work, but it will not only add unnecessary weight, it'll make the wood more brittle. Once a bit of super-glued wood breaks it is impossible to repair. Be warned!

Also frame up the rudder as well. I made a small alteration to the plan by going with a square frame instead of a swept back one.

Let the pieces dry for a while. Once they are set you can remove them from the baking paper or plastic wrap by carefully running a pin under the leading and trailing edges. Carefully use a fingernail file to sand the joints where excessive glue has dried. Then flip the pieces over and hit the bottom of the joints once more with some glue to make them stronger.

Once the glue has dried its time to add some dihedral to both the wing and stab. Dihedral is when you add an angle to wing at the centerline, lifting the wingtips up slightly at both ends. This adds stability to the model. Without it the model will yaw (turn) back and forth.

Lightly score the underside of the wing's and stab's leading and trailing edges. Pin one side of the wing and stab to the building board and crack the opposite ends up slightly. Slide a popsicle stick on edge under the raised side to prop up the wing and stab tips.

Place a good amount of glue at the center joint where you scored and cracked the wing and stab. Let this thoroughly dry.

While the wing and stab are drying, its a good chance to work on the fuselage. I used 2mm wood for the length of the fuselage then sanded it with a fine-grain sandpaper.

At about 50% back along the fuselage, I place a small hook for the rubber motor and fixed this in with super glue (for this super glue is ok)

Then I worked on the nose. I used a small piece of copper tubing (about 1mm) for the prop bearing and again fixed it on with super glue and wrapped it with thread to prevent it from coming loose.

Next I glued the rudder to the end of the aircraft. Again, I deviated from the plans slightly by mounting my rudder upside down under the stab. This will make it a lot easier to mount the stab later.

Once this dried I started the process of covering. I use normal tissue paper as the covering. It's pretty easy to work with so long as you have a sharp knife. Cut a piece approximately the size you will need. Then take a glue stick and carefully apply glue to one side of the rudder. Make sure that every bit is covered.

Then place the piece of tissue on your work table and place glue-sticked rudder gently on the tissue. Run your finger around the perimeter of the rudder, carefully pulling corners to iron out wrinkles.

You only need to cover one side of the rudder. Covering both sides will not afford the aircraft any advantage and will only serve to add additional unwanted weight to the airframe.

Let it rest for a few seconds as the glue dries. Then use a really sharp knife to carefully cut the excess tissue paper away.

Once the rudder has been done and the wings and stab have dried, its time to cover the rest of the plane. The dihedral makes covering the wing and stab a bit more difficult but not impossible.

Cover one half of the wing at a time. Don't try to tackle the whole thing in one go. The glue will dry too fast and you'll end up with a lot of wrinkles in the tissue and frustration.

Before you cut away the excess, make sure that the tissue is firmly attached all around the piece. Use a bit of PVA to close up any loose bits.

The final step is to assemble everything. The stab was mounted above the rudder and the wings on two sticks, which in turn were mounted to the fuselage according to the plan.

I added some wingtips using extra ribs and using the same process as the rudder, wing and stab for covering.

The prop was also made from balsa. The plan has a template for the blades. I used a 2mm x 2mm balsa stick to join the blades, each glued 90-degrees to each other. I drilled a hole at the center. I then bent a prop shaft from steel wire with a hook at one end.

I then slipped the shaft through the prop bearing on the fuselage, followed by a small bead as a prop bushing. Finally I stuck the prop on the shaft and glued the two together. Props are a bit complicated, perhaps deserving its own article altogether!

|

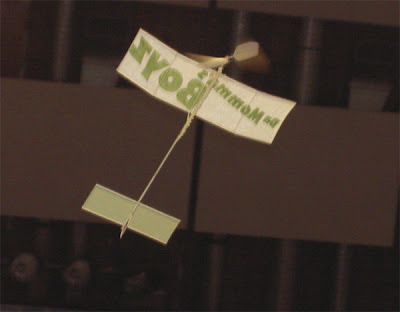

Completed model with rubber band motor attached. Weight: 1 gram.

|

To Fly

1. Test glide the model first. Apply noseweight (I use blu-tac or clay) until a nicely controlled glide is achieved.

2. Wind about 10 times for a low-powered test flight.

3. Trim model to turn left or right using rudder (add a small paper tab or carefully bend rudder).

4. When satisfied with the test flights, put a full 20-30 winds on the motor.

Thats it for me! Happy flying, and I'll be returning to our normal FoW content soon :)

Trimming and flying indoor involves a lot of trial and error, so persevering pays off in the end!

Cheers,

-M

Thats it for me! Happy flying, and I'll be returning to our normal FoW content soon :)

Trimming and flying indoor involves a lot of trial and error, so persevering pays off in the end!

Cheers,

-M

Ugh apparently words are hard. I think this is very cool and fascinating. I was surprised by the potential of your fancified paper airplane. Well done.

ReplyDeleteKeep these posts coming!

ReplyDeleteI love Flames of War but this reminds me of flying balsa planes as a kid.

Happy Days ;)

Cheers,

Allan

I have long been an admirer of your dad's work on the Wings of Glory forum and your post here reminded me of my father's contribution to indoor modelling here in Australia.

ReplyDeleteIf you have the time & inclination you may be interested in perusing this page (you will find Dad's contribution to the Hangar Rat story further down the page). My brother recently unearthed his original plans showing his mods to Harry's Hangar Rat.

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/hangar_rat.html

All the best

~Wayne

Hi Wayne,

DeleteThanks for the message and the link! Looks like a lot of fun, and also those plans for the hanger rat will be pretty useful! I'd really like to get into some indoor electrics. I might have to bump that up the hobby queue!

Cheers,

Mike